Multimedia Content

Flu Alert, 23 May 2009, courtesy of Andrew May, Private Collection.

Details

Influenza in Melbourne: How to guard against it!, 25 January 1919

Details

Influenza precautions leaflet, 23 November 1918, courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria, Victorian Archives Centre.

Details

Infuenza ward in local hospital, 1919

DetailsNurses with sick children, 1919, courtesy of Museum Victoria.

Details

Outbreak of influenza, 24 January 1919, courtesy of Public Record Office Victoria, Victorian Archives Centre.

Details

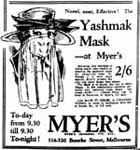

Yashmak Mask, 14 February 1919

Details

Swine Flu: In Focus - June 2009

- From

- 2009

- To

- 2009

H1N1 Influenza 09—or Human Swine Flu—has finally arrived in Melbourne, reviving memories of previous influenza outbreaks. Melbourne experienced flu as early as 1860, with epidemics in 1885, 1890-91 (‘Russian influenza’), 1899, and most famously during the ‘Spanish flu’ outbreak of 1918-19. As David Dunstan notes in his entry on ‘Health’, the outbreak of Spanish influenza ‘challenged the sense of security many considered their right as a consequence of distance and quarantine’. Victorian death rates reached 240 per 100 000. Twelve thousand perished Australia-wide, and globally the death rate of over forty million was more than mortality during World War I. In Melbourne, with hospitals unable to cope with the sick, temporary wards were opened in the Royal Exhibition Building and in schools across the city and suburbs.

In 1999, historian Geoffrey Blainey reflected on the twentieth century’s greatest tragedies (‘Bearing witness to history’s black moments’, Sunday Age, 25 July 1999, p. 6). As part of a ‘Poll of the Century’ published in the Age and the Sydney Morning Herald, the top five world disasters were voted by readers to have been the Holocaust, the bombing of Hiroshima, famine in Ethiopia, the Chernobyl nuclear accident, and the 1918-19 flu epidemic.

Australia’s top ten were listed in order as Gallipoli (1915), the Port Arthur massacre (1996), Cyclone Tracey (1974), the Granville Train Disaster (1977), the Ash Wednesday Bushfire (1983), the 1918-19 Flu Epidemic, the Black Friday Bushfires (1939), the Thredbo Landslide (1997), the Voyager/Melbourne Collision (1964), and the Westgate Bridge Collapse (1970).

Ninety years ago, early measures to combat the Spanish influenza epidemic included maritime and land quarantine, and the closing of the NSW/Victoria border. In November 1918, as Melbourne became first aware of a likely outbreak, over 11000 leaflets were distributed to households with information on precautions they might take to avoid contagion. The outbreak hit the city on 21 January 1919, and by the end of the month free inoculations were being given to over a thousand people a day.

The ways in which the city responded to the epidemic could reveal deeper religious and political differences. In an attempt to solve the problem of a shortage of nurses at the Exhibition Building hospital, Catholic Archbishop Daniel Mannix had offered the assistance of nuns, in addition to a suggestion that the mother rectress of the nearby St Vincent’s Hospital should take charge of the temporary facility. Sectarian uproar ensued. Reverend Worrall of the Methodist Conference railed against the possibility of non-Catholic patients being under the care of ‘a sacerdotally trained band of anti-Protestants’ (Hyslop 1996, 323). In political terms, propagandists could make the symbolic link between the epidemic and conservative fears of Bolshevism (Hoare 1919).

After the first cases of Swine Flu were reported in Melbourne in May 2009, a primary school in Clifton Hill was closed down for a week. In 1918-19, Victorian Government regulations also attempted to limit the possibilities of transmission by controlling the congregation of crowds in public spaces and places of popular entertainment. At the end of January 1919, State Cabinet ordered that all cinemas, theatres, concert halls and other public halls be closed within a fifteen-mile radius of the GPO. Church-goers could attend divine service, as long as they wore ‘a mask of an approved kind’. The Hawthorn Tramway Trust increased the minimum fare on some of its routes as a means of preventing overcrowding and therefore the risk of infection. James Hardie & Co. offered to supply municipal authorities with fibrolite asbestos cement sheeting ‘for the purpose of building Inhalation Chambers with a view to fighting the Influenza’. A special conference of municipalities urged that people engage in ‘quiet, cheerful life in the family and with a few friends in the home and in the open air away from crowds’.

It is likely that, as in Sydney, the inner city working-class suburbs of Melbourne experienced higher rates of mortality during the Spanish Flu epidemic than more exclusive suburban belts (Camm 1984). Working-class men and women were also more vulnerable in terms of losing their jobs due to illness, and families were placed under increased financial burden when breadwinners were sick or died. Such serious social impacts contrasted with fashionable ‘inoculation parties’ as well as humorous newspaper articles that minimised the risks of infection.

The mass media plays a pivotal role in shaping popular perceptions of catastrophic events, and the ways in which journalists describe disasters may have a direct effect on public or political responses. The genre of disaster coverage can often simplify events by drawing on a repertoire of common themes (such as survival stories, national unity, state blame, visits of politicians, generosity of helpers). In 1918-19, some newspapers exaggerated popular fears of the new ‘plague’, while newspaper advertisements played on the public’s fears—failure to take Hearne’s Bronchitis Cure ‘may result in this dreadful Plague ravaging its way throughout the whole of Australia’ (Argus, 27 February 1919, p.8). Others complained however that the panic about influenza distracted attention from more pressing concerns such as the spread of venereal diseases.

The list of local, national and international disasters will always need updating. The 9/11 attacks (2001), the Bali bombings (2002) and the Black Saturday bushfires (2009) would no doubt appear on current lists. The memory of catastrophe is not always determined by the death toll. As Geoffrey Blainey noted, many twentieth-century disasters were seared into the popular memory because of the proliferation of mass media reportage and the power of photographic imagery. The Swine Flu epidemic is yet to run its course, but if Melbourne’s experience during previous epidemics is any guide, media discourse will play a leading role in how it is conceived and managed.

Responses to the 1918-19 flu epidemic can be seen in terms of a range of issues, including colonialism, sectarian sentiment, and recovery from war. Current political, cultural and public health responses may reveal to future historians our own particular social preoccupations and divisions over issues such as civil liberties, globalisation, and border security.

- References

- Camm, Jack, 'The "Spanish" Influenza pandemic: Its spread and pattern of mortality in New South Wales during 1919', Australian Historical Geography, no. 76, 1984. Details

- Cumpston, J.H.L., Health and disease in Australia: A history, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1989. Details

- Hoare, Benjamin, The two plagues: Influenza and Bolshevism, Progressive and Economic Association, Melbourne, 1919. Details

- Hyslop, Anthea, 'Fever hospital', in David Dunstan (ed.), Victorian icon: The Royal Exhibitjon Building Melbourne, The Exhibition Trustees, Melbourne, 1996, pp. 320-7. Details

- Hyslop, Anthea, 'Epidemics', in Graeme Davison, John Hirst and Stuart Macintyre (eds), The Oxford companion to Australian history, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1998, pp. 220-2. Details

- Hyslop, Anthea, 'Insidious immigrant: Spanish influenza and border quarantine in Australia 1919', in S. Parry and B. Reid (eds), Migration to mining: Collected papers of the fifth biennial conference of the Australian Society of the History of Medicine, Darwin, July 1997, Northern Territory University Press, Darwin, 1998. Details

- McQueen, Humphrey, 'The "Spanish" influenza pandemic in Australia, 1918-19’', in Social policy in Australia: Some perspectives 1901-1975, Cassell Australia, Sydney, 1976, pp. 131-47. Details

- Taska, Lucy, 'The masked disease: Oral history, memory and the influenza pandemic 1918-19', in Kate Darian-Smith and Paula Hamilton (eds), Memory and history in twentieth-century Australia, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1994, pp. 77-91. Details